Would you rather your child run wild at Forest Kindergarten or cram for tests in a classroom without recess? The film NaturePlay takes a close look at two divergent educational trends.

Overseas Singaporean mama Adrienne Goh has regularly written for us about her experience living with her husband and daughter in Copenhagen, Denmark. Today she provides an in-depth review of the fascinating documentary film NaturePlay, which contrasts the benefits of the Scandinavian system of forest kindergartens and outdoor learning with the American trend toward educational testing (which she feels has many parallels to Singapore).

I was recently invited to watch the film NaturePlay – Take Childhood Back, and what a privilege it was.

NaturePlay is a documentary that explores Scandinavia’s educational system – its philosophy and approach around learning, living and enjoying nature – and contrasts it against the high-stakes, standardised testing culture in the American school system.

The film does not rush, neither does it insist, but it gently invites viewers to consider what exactly is at stake when society pursues a numbers-driven, test score-focused educational system. The film also liberates, and it inspires viewers to reflect on the kind of childhood we dream of for our children, and what we can do to help them take back their childhood and education. And all of this, wrapped up in stunningly gorgeous, lovingly shot cinematic portraits, from the forests in Denmark to the fjords in Norway.

To What End?

NaturePlay sets the tone within the first 10 minutes, and we are made highly aware of the challenges many US school systems face – and they are very much similar to those confronting the educational system in Singapore.

With the increased emphasis on data as proof of acquisition of knowledge, school systems have been redesigned to drive test scores. Teachers are put under high pressure, and they face an almost “ethical” dilemma, caught between what they believe is important in nurturing the child’s love for learning, and having to “teach to the test” because higher test scores are thought to prove their teaching and the child’s learning.

Recess has been taken away altogether in some American schools, in order to have more time to teach just to achieve higher test scores. In an interview, it is unsettling to hear a mother recount how her son had never had recess in his public school.

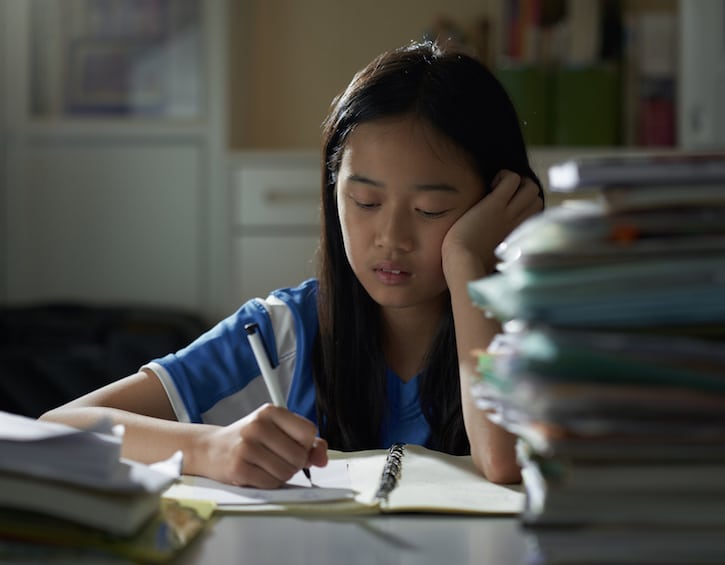

Children in the US are increasingly stressed about going to school, homework and tests. More are suffering from anxiety, depression, ADHD and obesity. Parents, unable to break away from the system, have little choice but to “surrender” and engage extra teaching (or in Singapore, euphemised as “enrichment classes”) for their children to achieve better scores for these “all-or-nothing” tests.

“Education and children and nature belong together”

It is almost a literal breath of fresh air when the film crosses over to Denmark, examining in detail the concepts of “friluftsliv” (literally, ‘open-air living’) and “udeskole” (outdoor education) – Scandinavian outdoor life and education.

The film leads us into forest kindergartens, outdoor schools, and playscapes where viewers get a glimpse into how these elements meld together. Through insightful interviews and conversations with parents, researchers, teachers, architects and even legislators, it is evident that the Danes have acknowledged and internalised the belief that “education and children and nature belong together.” Not a fad nor a trend, but the cornerstone of Scandinavian living, so deep-rooted in thinking and ingrained in culture that it not only permeates their daily lives, but also informs their parenting methods and approach to education.

The Danes recognise the importance of learning in different environments, and because nature provides plentiful opportunities for children to learn holistically and to experience learning involving “the head, the heart and the hand,” a huge proportion of teaching time is spent outdoors in nature. As observed by a Danish principal, “It is naive to think that you can only learn from reading a book.”

The move away from a classroom-based education to one outdoors has not only been driven bottom-up. It has also seen tremendous support and investment from the Danish Ministry and the Municipalities. In my opinion, government leadership is possibly the lynchpin to the success this educational approach has experienced in Denmark.

Without fundamental policy changes to the US education system – the philosophy, objectives and measures of success (right down to the teachers’ key performance indicators) – parents and children who deviate from the system will find themselves disappointed, demoralised and exhausted over time. Symptoms of this classroom-based, test-score focused malaise may be treated from time to time (PSLE T-Score, anyone?), but it is the foundational framework of the system that needs to be rigorously scrutinised and completely overhauled.

Forest Kindergartens

My daughter attended a forest kindergarten when we moved to Denmark in 2013. Sara was 3.5 years old, and our experience with those kindergarten years left us with an incredibly deep impression. A defining feature of forest kindergartens is that children spend all day outdoors, in all seasons – rain, snow, sleet or shine. And research has shown, unequivocally, that spending time outdoors is great for a child’s development. Children are fitter, they concentrate better, and there is more social interaction and play. Simply put, children are happier.

In the film, we see children in a forest kindergarten, running around freely, climbing trees and “scaling” hills. They are given knives and saws, and they are taught how to use them properly. They play around comfortably with dirt and mud, using spoons to dig into streams. By being exposed to nature’s elements, they learn to engage with nature instead of being fearful of it.

But we learn that this approach is not confined to forest kindergartens. Regular kindergartens in urban areas incorporate being outdoors as much as possible. Excursions into nature are part of the regular kindergarten “curriculum,” and on any given day in Denmark, if you are taking the bus or the metro, you are likely to bump into groups of (uber cute) little kids going on excursions.

Learning Outdoors

Time spent outdoors isn’t just reserved for the little ones. There is substantial investment in nature and environmental programmes for older children throughout the formal public education system, with the aim to inculcate their appreciation for and enjoyment of nature, complete with plenty of hands-on activities.

When learning in nature, it is not merely learning about nature. It is learning about other subjects as well, but in a different environment that stimulates all their senses in learning. This creates a more authentic connection between the subject and the child, where the child gains a deeper understanding of the topic, and this complements what is being taught inside the classrooms.

The film next journeys to Norway. At the start of the new school year, it is common for high school classes to go on outdoor nature excursions. Nature excursions are quintessential icebreakers – as you struggle through physical challenges together, you have no choice but to interact and help one another. Common shared experiences form the basis of new friendships to be made. Perhaps best of all, as perfectly articulated by a Norwegian high school teacher, “You find your value as a person in nature, because of the fellowship which grows out of these challenges and doing them together.”

The dads in Sara’s class have taken it upon themselves to organise an overnight nature camp for the kids at the start of each school year (which strangely coincides with moms’ night out). After a seven-week long summer break where the kids do not get to see much of one another, this “Daddy-Child-Camp” hits all the right notes in terms of renewing friendships and enjoying the company of friends in nature.

Playgrounds Matter

In our first year in Denmark, I struggled with being a Stay-At-Home mom (SAHM). Housework skills aside, my mothering skills were substandard at best – I was at a loss as to how to take care of and “entertain” Sara all day. Maternal instincts never kicked in.

There was a large and fun playground near where we stayed, and we spent copious amounts of time there because I did not know what else to do. One day – the penny finally dropped – I decided that we could also spend copious amounts of time at other playgrounds. And it would be a perfect way for us to get to know the city.

I found a “playground map” on the official Copenhagen website. It not only listed the more than 125 outdoor playgrounds in Copenhagen and their addresses, it also gave brief descriptions of the play structures available (swings, sand pit, slide, zipline, etc) and the appropriate age group! Of course, listing nearby café options would have propelled the map into A-list map status…

Over the next two years, Sara and I systematically checked off that list, and the playgrounds we encountered were all wonderfully different, engaging and clever. (I also became cognizant of the privilege and luxury of being a SAHM, taking her out of kindergarten once a week, just to spend time together.) During this time, we discovered, as part of Copenhagen’s adventure playground repertoire, “Nature Playgrounds” and “Junk Playgrounds.”

The film interviews Danish landscape architect Helle Nebelong, from whom we learn of Copenhagen Municipality’s attention to creating diverse and inspiring playgrounds. There are 22 Nature Playgrounds – playscapes involving lots of nature elements with trees, logs, plants, boulders, sand, hillocks and many “loose parts”. This creates an environment where children “get into contact with their own body” – when balancing on logs, climbing trees, or running up and down knolls.

Interestingly, Helle points out that the loose elements – sand, water, pebbles, berries, acorns, etc. – are the most critical because they are what inspire how children invent their plays. The loose elements are dynamic and unpredictable, and they create a vastly different playing experience from playing on standardised, flat, rubber-surfaced playgrounds.

The film gives us a splendid taster of a Nature Playground – the “Valbyparken Naturlegeplads” designed by Helle. I can attest that it is as amazing in real life as it looks on film, and honestly, even more so. Sara devoted numerous afternoons exploring the sprawling playground as a toddler and pre-schooler. In primary school, her class went on several memorable field trips to Valbyparken, and Sara even held a birthday celebration there!

Junk or Jewel?

The film further emphasises the relationship between learning, playing and nature by showcasing Denmark’s “Junk Playground” concept. A Junk Playground is characterised by having good opportunities for children to develop creative outdoor play. The play is uninterrupted by adults, and there is a general absence of traditional, rigid play equipment and structures designed by (adult) architects and engineers.

Instead, Junk Playgrounds are designed and built by older children, from ages 10 to 14, guided by trained pedagogues or assistants who ensure basic safety guidelines are adhered to. Children can play with “dangerous” tools, but only if the pedagogues have agreed on when, where and how. The pedagogues also do not over-instruct because “being allowed to fail is important…failing is key to learning and becoming wiser.”

To this end, Junk Playgrounds are littered with recyclable and scrap materials, such as corrugated boards, pallets and wood blocks. Children work together to hammer, saw and construct tree houses, rafts, slides, ramps and play structures. Beyond technical woodwork skills, children also develop soft skills in negotiation, responsibility, communication and commitment.

It’s almost unfathomable but the idea of Junk Playgrounds (“Skrammellegepladsen”) was first mooted way back in 1931 by Danish landscape architect Carl Sørensen. He observed that children played everywhere and not just in playgrounds; particularly on construction sites, children were essentially creating their own playscapes. In 1943, the first Junk Playground eventually opened in Denmark (which – fun fact – led to the construction of the first British Junk Playground), defined by the ethos that “play should be self-directed and children should be allowed to pursue their own projects without adult interference.”

Denmark continues to lead in the number of such playgrounds, although we now call them Construction-/Building- Playgrounds (“Byggelegeplads”). Countries including England, France, Germany, Japan, and Switzerland also have a fair number of these.

It is therefore no surprise that Sara’s GOAT (Greatest Of All Time) playground is a Construction Playground near where we live. While she doesn’t get to build the playground (one must be enrolled), the adrenalin and exhilaration she gets out of playing there tops all other playgrounds. It makes perfect sense – children know children best. Caveat emptor: if you’re planning to make a dash for it, the Municipality makes it clear to parents that “the construction playground area is not designed according to the safety rules for ordinary playgrounds.”…which brings us to the Scandinavian approach to risky play.

Approach to Risky Play

Children are natural explorers, they are curious and open-minded, and the outdoors provide limitless possibilities to slake their thirst for adventure, freedom and independence. Playing outdoors is perceived as a natural form of risky play, and Scandinavians view this risk as an opportunity to develop.

When children are exposed to a little risk, they get a chance to explore their boundaries, confront their limitations, and challenge themselves appropriately. They learn to trust their instincts. At Sara’s forest kindergarten, because risky play was encouraged, minor injuries were par for the course. The pedagogues rarely interrupted the children’s play, but I noticed at least one pedagogue was always observing from the side – “behind the children” – looking out for their safety.

As parents, our instinct when looking out for our children is often yelling, “Be careful!”, “Stop!” or “It’s raining, come back in!” We have become experts in childproofing our environment because we feel a need to protect our children from getting bruised, wet or cold, instilling in them unnecessary (at most times) fear and self-doubt. As a teacher wryly notes, “I’ve never met a child who got so wet that they couldn’t get dry again.”

“Learning is about so much more than test scores”

The film quietly circles back to the crux of the issue – our growing obsession with tests and driving test scores, at the expense of our children and their relationship with learning, living and enjoying nature.

There are national, standardised tests in Denmark. Following continued disappointing PISA results (pfff and don’t get me started) and in line with OECD recommendations, the Danish educational system underwent a massive reform in 2010. Integral to the reform was a compulsory national test programme, covering a total of 10 standardised tests from grades 2 through 8.

These tests are online, self-scoring and therefore independent of any subjectivity or bias in marking. They are also adaptive, meaning that the child is presented with questions of varying difficulty based on a continuous assessment of the child’s proficiency level.

Unlike regular linear tests, it does not matter how many questions the child is able to answer correctly. Instead, it is the difficulty level of the correctly answered questions which are evaluated, and this results in a more accurate reflection of the child’s understanding of the material.

To address strong concerns that these tests would promote “teaching to the test” or worse, demotivate children and skew their attitudes towards learning, these tests cannot be studied for. It is not a memorise-and-regurgitate competition; the children either know, or they don’t. Sara did not (and could not, even if incentivised) study for these tests. This also meant that there was zero stress leading up to test date; my husband was not even aware these tests existed till much later.

I belabour this point because this topic is close to my heart. Even to this day, the Danish standardised tests continue to fuel passionate debates within the community. It is certainly of crucial importance we question and determine the rationale behind testing our children. Teachers should be able to use tests scores as tools to evaluate how effective their teaching has been, and to help our children learn better by providing one-on-one feedback.

Tests should not be used “to screen” or “to stream” young children according to their grades. It is heartbreaking to read about the rising number of children seeking therapy because they are too stressed and are unable to cope with academic pressures and expectations. Sadly, some go on to view their test scores as a reflection of self-worth. This has got to stop. We need to do more to help our children develop a healthy view, not only towards tests, but much more than that, a healthy and joyful attitude and behaviour towards learning in general.

What Needs to Change

NaturePlay ends with a moving rallying call to the people in positions of influence who I strongly believe should take the lead in overhauling and restructuring what is now a deeply entrenched, high-stakes, test score-focused educational system.

“When designing education policies…stay focused on the process of learning, stay focused on the child.” We would be terribly remiss to focus only on the “end product” – gearing and optimising our educational system to generate higher test scores – which ironically and tragically will be (mis)used to measure and prove the success of the very educational system we should move away from.

A Post COVID-19 Silver Lining

With kindergartens and schools around the world looking for safe ways to reopen post Covid-19, Denmark may offer up some solutions as one of the first countries in Europe to ease the lockdown.

Kindergartens and primary schools reopened mid-April, and it was a little bit of a whole new world with the health and safety guidelines schools had to abide by. A distance of 2 metres between desks in classrooms was imposed and recess was organised in batches. Children could not be in groups of more than 2 while inside and 5 outside. No hugging, no kissing, and hands were, of course, regularly washed. (Unlike the rest of the world, no face mask requirement, though!)

Children in different grades started classes at slightly different times, entering schools at specific entrances to help limit the number of people arriving at the same time. Parents were strictly not allowed to enter the schools’ premises or playgrounds. There were also designated pick-up spots for each class outside the schools.

Most of these rules have been relaxed a little. The key guidelines around hand-washing and physical distancing are still in place.

It is a huge challenge to create enough space to adhere to these distancing guidelines. Therefore, many schools are now holding a large proportion of their classes outdoors, or even in nature – a completely unintended but 100% positive externality.

Sara now spends up to 3-4 hours each day outdoors – in the school yard or in the sprawling parks near her school. This amounts to half her school day spent outdoors or in nature. Her teachers have reshaped the curriculum, devising creative ways to teach in nature: for example, they have blended Math and Art through “Nature Mandalas” and “Street Art” projects, as well as Danish and Physical Education through treasure hunts and games. And the rest of the time? Free play, but of course!

NaturePlay has won seven international awards, including a Global Humanitarian Award and one for Cinematography. If you are an educator or a community passionate about nurturing the relationship between children, nature and education, this thought-provoking documentary will resonate with you.

In light of the current pandemic, there is now an opportunity to set up a virtual community screening of this film! Drop an email to [email protected] about obtaining a community screening licence and hosting a virtual screening for friends, families, colleagues and communities. Visit the NaturePlay website at www.natureplayfilm.com for more details!

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All