Children, especially girls often have a desire to be liked and fit in. One mom of four discusses her child’s behavioural changes as she navigates the tricky stages of trying to ‘blend in’ to social groups at school

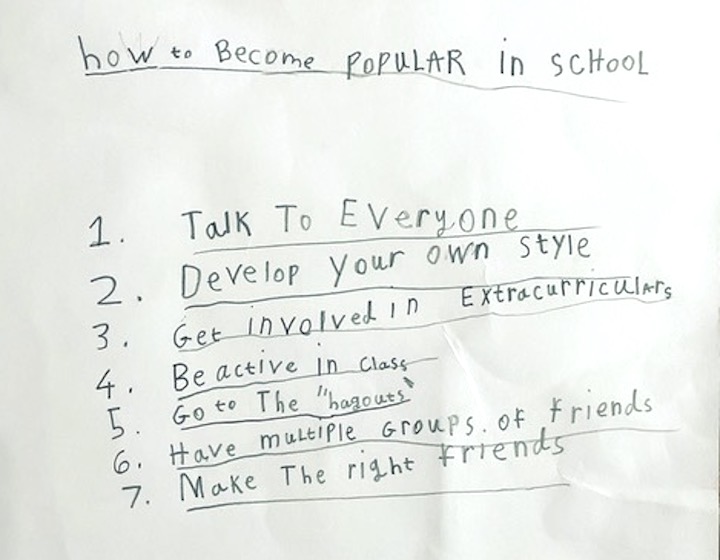

One morning when sorting through the rats’ nest of paper in the art box in Hetty’s room, I found a large sheet of paper buried under a myriad of drawings of cute dogs and girls with long eyelashes and big hearts emblazoned on their T-shirts. The titles of the sketches were things like ‘Shopping with my BFF’ and ‘The Sleep-over’. Hetty (9) is constantly drawing, copying, following instructional craft videos and there are reams of pictures under similar themes but this one was different. It was a written list under the heading, ‘How to become POPULAR in school’. At first glance I was blown away by the very measured and sensible strategies which genuinely filled me with pride and delight. Sage advice like “develop your own style” and “have multiple groups of friends”, and the endearing misspelling of hangout to ‘hagout’ made me chuckle.

However, for a couple of days subsequent, I couldn’t shift the niggle surrounding the word ‘POPULAR’ written in capital letters on the top of her page.

Is she worrying about being popular?

So, I left it on the table for when Hetty came home from school and she noticed it there.

“What are you doing with that?” she questioned.

“Oh, I was clearing the art box and found it in your room this morning and it looked important, so I am curious who it was for?” I tried to say nonchalantly.

“Just anybody really, who wants some advice…”, she shrugged and continued to tuck into her peanut-butter spread sandwich.

I probed a little further,

“There is some lovely advice here Hetty. I know so many people who will want to read this and find it helpful. But I am really wondering what becoming popular means to you? Can anyone be popular?”

She gently placed both hands on to her lap, straightened her back and inhaled deeply as if launching into a rhetorical speech,

“Well, it’s not about being perfect, but you do have to look nice…. maybe have some cool accessories… I think that you are lucky if you are popular.”

Read More: Differently Wired Kids: To Label Or Not To Label? One Family’s Story

Fitting in and the added complexity social media brings

If this is true and luck does have a bearing on our children’s social interactions and experiences, then no matter how much we worry, engineer and step in, our child’s successes in the friendship landscape may purely depend on old school fate. Sadly, in our modern fast-paced, quick fix, “fake it till you make it” world, this doesn’t marry up with the message that our children are receiving. Arguably, most of us, if questioned would probably admit to trying to fit into the IN-crowd at least once, or revering those who we deemed to be ‘cool’, ‘popular’ or ‘in vogue’. Those terms in themselves are probably completely ‘uncool’ now. However, if we add in, social media with private groups, maps that track where and when friends are meeting each other, interactive games with tournaments and competitions against complete strangers… then we are entering a whole different realm of rules, lingo and social etiquette which seem impossible to keep up with. Gordon Neufeld and Gabor Mate names all of this in their excellent book “Hold on to your kids: why parents need to matter more than peers” when they say,

“Children are not quite the same as we remember being… Sometimes they live and act as if they have been seduced away from us by some siren song we do not hear…We struggle to live up to our image of what parenting ought to be like”.

Read More: A Mother’s Open Letter To Her Daughter with Autism

Autism adds another layer of complexity to trying to ‘fit in’

For children like Hetty who has an Autism diagnosis, this also adds another layer of complexity. She didn’t speak with any fluency until she was over five years old and pretty much learnt her mother tongue as if it was a foreign language. She scripted most of her words with parrot-like mimicry and since she has been in mainstream education, she still requires social/emotional literacy support behind the scenes to regulate her worries and anxieties and understand herself. On the outside, she is a sociable, empathetic and imaginative nine-year-old who has made huge leaps in her development from the non-verbal, screaming vessel of terror and frustration we spent her early childhood navigating. Her communication has opened up the magic in her personality, proffered opportunities for integration but also revealed the mighty power of peer orientation. The clues were there that Hetty was ‘learning the language’ of peer relationships during her play therapy, but day to day, there were also behaviours that ran comorbidly, which needed reframing and investigation.

Regressive behaviours can be a clue that a child is anxious or worried

For instance, last year she was finding things tough at school due to an over-zealous need to be accepted. This manifested in fervent space-invading tactics: following, copying and people-pleasing. The rejection was painful but we only really became aware of the full brunt of its impact when certain quirks and traits we hadn’t witnessed for a couple of years returned. Hetty has always stimmed (self-stimulatory behaviour) in varying degrees of intensity, but we were noticing her laugh to herself – high-pitched and random and she would also run full-pelt, American football style shuttles back and forth across the living room. When she was little we used to call it her “giggle wiggle” and Riley, my eldest son, was the first to notice,

“The giggle-wiggle is back!” He exclaimed.

Then he and Bruno, my younger son, got out of their seats (anything to escape the meal table!) and started to chase her; then we all joined in, sending the dogs completely bananas, and it became a game. Hetty squealed with excitement, the expression softened in her face, her body relaxed and she came back to the table to finish her food. The act of running, moving and expelling pent up emotional energy briefly shifted the build-up of hurt and rejection. The playfulness in joining her in the game normalised it and didn’t draw attention to her obvious quirky mannerisms which would have likely made her more self-conscious and expose her differences.

However, in the back of my mind, lingered statistics such as 70% of Autistics will suffer from a mental health challenge and 40% will suffer from anxiety (youngminds.org.uk), so I am fully aware of what we may be up against. Regressive behaviours in children can be a clue that a child is anxious or worried or finding things challenging. For instance, some children who are completely functional in their toileting can start to soil themselves or the frequency of the bathroom visits start to increase. Some children start to avoid eating or be very picky about what they eat, after being relatively easy eaters, and others will find falling to sleep a challenge and have interrupted nights.

The other clues we witnessed which suggested that Hetty was becoming more aware about fitting in were centred in her vocabulary and affect. I would catch her in the mirror practising phrases like,

“Whatever!” (With a flick-of-the-wrist, dismissive hand gesture) or “Wow! That’s so aesthetic!” (I still am learning what that means.)

The first time I was on the receiving end of “Whatever” I raised my eyebrows in only the way that parents can and she stopped in her tracks; the body language dropped, the American teen actress was gone and she melted into Hetty again,

“Sorry Mumma, is that rude? What does “whatever” mean?”

By breaking down the facade, she was questioning her own word choices without properly knowing what it all meant. Children see and hear a lot of things that they don’t understand or process properly, be it in school, on screen or out and about, but their focus on their image management can hide their insecurity or immaturity. Breaking down their language, understanding its intention and the emotional impact it has on you or others, can model that self-reflection about the cause and effect of their actions and words.

The need to ‘blend in’ socially

Hetty is very in-tune and transparent about her challenges and her diagnosis as we told her about her Autism very early on. However, to what degree she instinctively feels that to survive socially she must blend in, remains to be seen. She declared that dolls and barbies are babyish and she wanted them moved out of her room, even though behind closed doors I would see her happily playing with them with my younger daughter, Trudy. She also refused to wear dresses, and wanted to go shopping for a frightening combination of leopard print, denim skirts and crop tops.

Read More: “My Son Has Special Needs. He Has Taught Us So Much”

For children with Autism, the need to be accepted can be on a whole other level

Hetty seemed to be ‘masking’ something. Masking is a common term in the Autism sphere as it describes a few behavioural tropes. For instance, if the lights are too bright or a noise is too loud, most children will express that they are finding it tricky to concentrate but when that social communication is not as robust, some children won’t express it to deliberately camouflage their discomfort. That deliberateness can suppress parts of themselves as a cost to morphing into the crowd. Alternatively, it may manifest with children starting to mimic a particular accent, mannerism or style of somebody they’re spending a lot of time with. We all know that children have a desire to be liked and fit in at a certain age, and it is often prevalent with girls, but for children with Autism, the need to be accepted can be on a whole other level. Their mental stability can waver if they let their guard down. Engagement in lessons can be affected while they are processing every detail and plotting and planning their next moves, which can be exhausting. As a result, some children may go into over-whelm and act out at home where they can perhaps release the tensions of the day with safety. Sometimes there can be a disconnect between what the school may be seeing and what a parent may be experiencing, or vice-versa.

It’s good to notice and be curious about changes in your child’s behaviour

Whether or not a child is on the spectrum, the curiosity for why a change in behaviour or alter in mood, affect or personality is happening is always worth a look. Talking and working with your child and the school may help to understand the other side of the story and may reframe the reactions and strategies to deal with certain behaviours. The multi-agency support during a child’s formative years can be empowering and comforting for parents, as it can be a very lonely place. Parents often worry about when the right time to ‘step in’ might be, and that is largely personal, but involving your child in that decision-making may steer you in the right direction using a simple check-in like,

“Can you handle this?” Or “Who would you ask if you needed help?”

Neufeld and Mate call this “collecting the child” because in trusting your child’s tolerance for situations and sitting with an unconditional regard for their experiences will regulate their nervous systems, even if they haven’t the tools to express what they are feeling verbally. It is tough for parents or carers as there is no magic bullet, no ‘ one size fits all’ approach to peer relationships but to coin the well-known mantra of the iconic Michael Rosen,

“We can’t go over it, we can’t go under it, we’ve got to go through it”… Together!

Read more:

Differently Wired Kids: To Label Or Not To Label? One Family’s Story

Sassy Mama’s Guide to Counselling and Therapy in Singapore

Play Therapy for Kids

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

View All

![[𝗦𝗔𝗩𝗘 𝗧𝗛𝗜𝗦] 𝗞𝗶𝗱-𝗔𝗽𝗽𝗿𝗼𝘃𝗲𝗱 𝗗𝗲𝘀𝘀𝗲𝗿𝘁 𝗦𝗽𝗼𝘁𝘀 𝗬𝗼𝘂 𝗖𝗮𝗻 ‘𝗘𝗮𝘁 𝗳𝗼𝗿 𝗙𝗿𝗲𝗲’ 𝗪𝗶𝘁𝗵 𝗖𝗗𝗖 𝗩𝗼𝘂𝗰𝗵𝗲𝗿𝘀! 🍦🍩🧁😉

Before you ask “Can use CDC voucher?” Yes, you definitely can! These spots are perfect for an after-school treat, weekend fun, or just saying “yes” to dessert without saying goodbye to your wallet.

Comment “Sweet” or tap the link in bio for more foodie recommendations!

Got a fave kid-friendly spot that accepts CDC vouchers? Let us know in the comments too!

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

#CDCVouchersSG #SGMumLife #KidFriendlySG #FreeDessert #HeartlandEats #SweetTreatsSG #SGParents #FamilyFunSG #WafflesAndIceCream #BudgetParenting #ThingsToDoWithKidsSG #SGCafes #SupportLocalSG #KidsEatHappy #CDCAdventures](https://www.sassymamasg.com/wp-content/plugins/instagram-feed/img/placeholder.png)